Artworks of Derrick Macutay

Malvar's approach to guerilla warfare was elegantly simple. Troops were expected ambush the enemy, disrupt supply and communications networks, and hide.

Most contacts with the enemy were to be brief, most units making contact were to be small, and before launching any ambush, commanders were required to make certain that they stationed men along roads which the enemy might use to send reinforcements and that their own troops had easy access to escape routes.

Operations were designed to annoy the Americans and not produce a decisive battlefield result. Malvar did not want his own forces to absorb heavy losses in them.

For the U.S. soldiers stationed in Batangas, the war was frustrating. The Batangueño forces generally restricted their offensive operations to ambushing small units and escort parties and conducting hit-and-run raids on the American posts. With great regularity, they disrupted the American's communications system by cutting down telegraph wires. Hence, the Americans faced an elusive enemy -- one willing to fight only when he had a decisive advantage and who, when he lacked such an advantage, was content to hide.

Of these skirmishes, the ones started by the Filipinos followed familiar patterns. Generally, one or two companies of Malvar's men attacked a small group of Americans -- an escort party, a wagon train, a scouting party. After firing a few shots, the Filipinos scattered. Also, from time to time, a Filipino unit sneaked into an occupied town, briefly attacked an American garrison and then withdrew.

(From Aguinaldo's Memoirs)

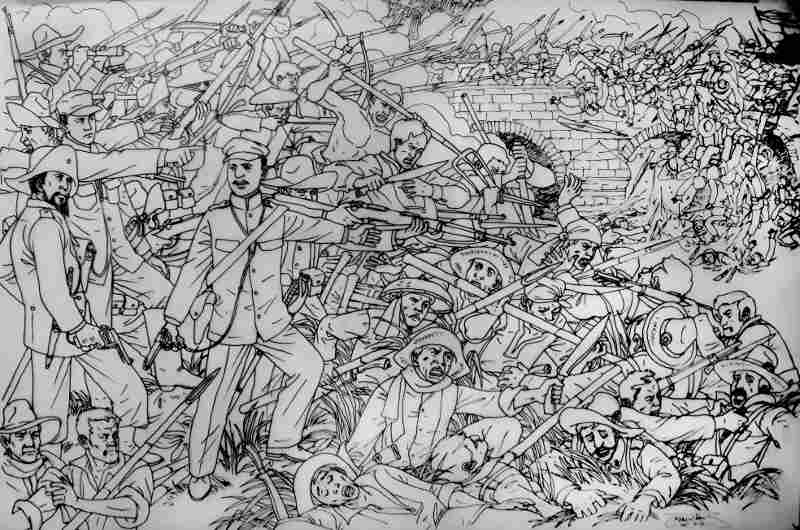

Then, on February 16, we heard that Captain-General Polavieja was at Palanyag (now Parañaque) church ready to attack Cavite. However, the newspapers in Manila published that the attack would be made at Silang. I did not believe the news, for I thought it was only a strategy of the enemy to make us leave Zapote and concentrate on Silang until I learned later that the troops we saw passing by Las Piñas were placed under the command of General Lachambre who was to direct the attack on Silang from Santo Domingo in Calamba, Laguna. I was sure our troops in Silang would not be defeated as our brave General Vito Belarmino would surely defend the town. Even with this information, I did not leave our stronghold at Zapote where I had selected brave generals, Edilberto Evangelista, Pio del Pilar, and Mariano Noriel.

While in the bitter fighting in Silang, our men fell right and left, one very disconcerting event happened to us when we were surprised by some Spanish troops who came from nowhere near Ligas at Zapote. So our men jumped at the enemy im hand-to-hand fights, using bolos, spears or any other weapons they had. Shots rent the air as our men pounced like lions upon their prey which had to retreat to the other side of the river. Again the Zapote river was drenched with the blood of both our soldiers and the enemy's.

Amidst the victory, however, I was greatly saddened by the loss of one great leader, General Edilberto Evangelista, and many Filipino soldiers.

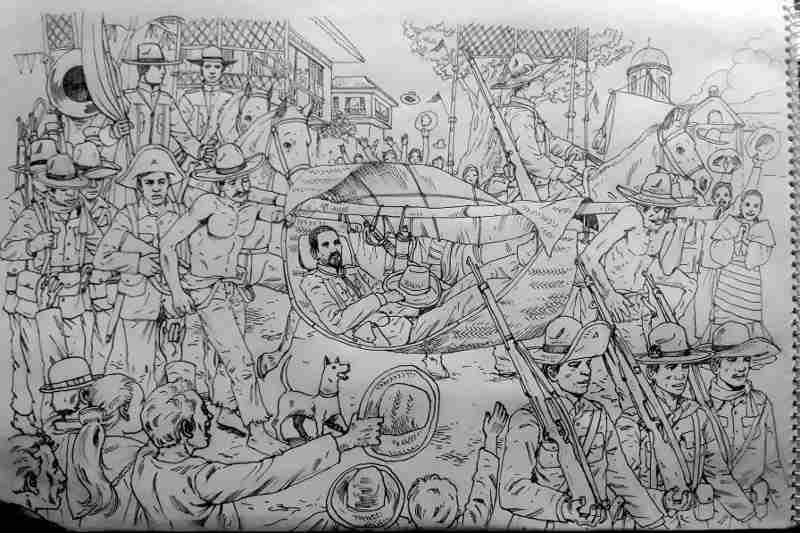

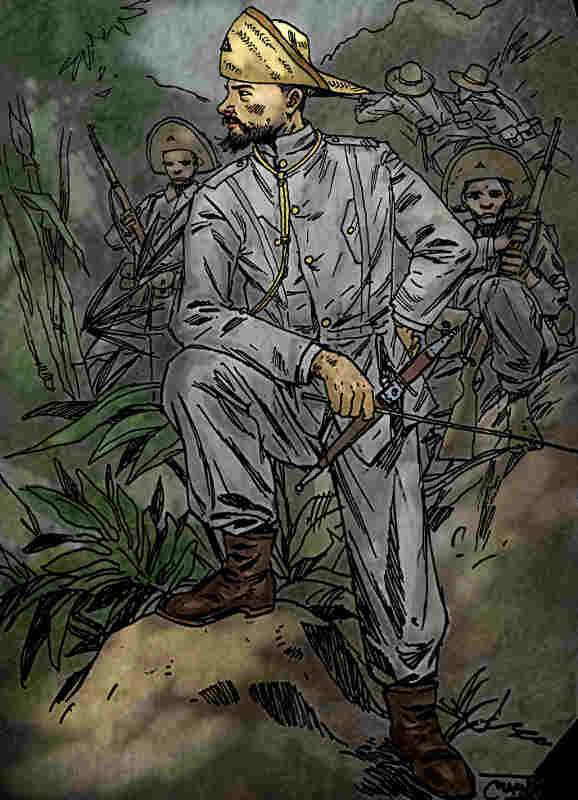

And on a bright and splendid sunny morning after the faintest of light clouds had gone, the sound of bugles and drums on the Tanauan side, made us presume that the previous months’ notice was going to be confirmed. We hurried up to the window, and ... Ecce homo! I mean, Ecce Malvar (Behold Malvar)! Modest pomp preceded him as if he wished to enter almost incognito; a half company of guerrillas and a few horsemen; behind them, the brave chieftain, not as a triumphant General, controlling a spirited steed, but as an august Malayan Caesar, weary of laurels, reclining in .... a modest hammock, held on the not very robust legs of white captives, formerly dashing Spanish soldiers. The Villa could not hide its deep joy and rang the bells at dizzying speed and the inhabitants rushed through the streets and plazas to cheer and hurray the hero."

- Translated from the memoirs of Dr. Santos Rubiano Herrera, Spanish medical doctor and prisoner of war in Lipa, October 1898. Translation by Renz Katigbac.

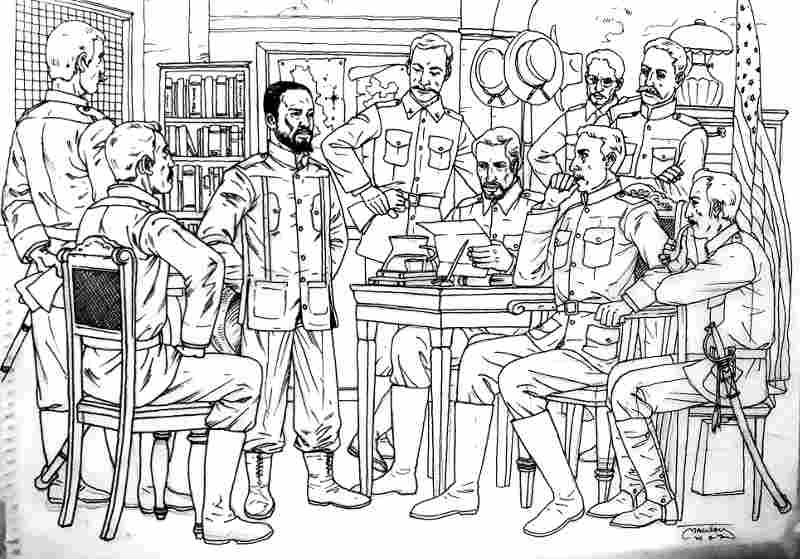

On August 13, 1898, the 56th day of the siege of the Spanish garrison by General Miguel Malvar's army, Commander Pacheco finally lowered the Spanish flag and raised the white flag of surrender at the tower of the church in Tayabas.

The Spaniards sent two Spanish officials and one Filipino in the person of Don Sofio Alandy to the headquarters of General Malvar in Mateuna to prepare the “Acta de capitulación de la Plaza de Tayabas”. Tayabas was finally liberated. The Spanish government in the province was overthrown.

General Aguinaldo had resumed the fight against Spain upon his return from exile in Hong Kong. Commander Pacheco, the Spanish military chief of Tayabas, had ordered his forces, scattered in the different garrisons of the province, to withdraw and consolidate in the city of Tayabas, the capital. The 459 men and 22 officers of Batallones de Cazadores numeros 10, 11 and 12 of the Regimiento de Tarragona enclosed themselves at the Casa Real, Tribunal, Carcel Publica, Church, and convento.

General Miguel Malvar arrived in Tayabas, together with General Vicente Lukban, Eustacio Maloles, Dr. Roxas, and Colonel Aniceto Ortega, to lead an army of 13,000 to 15,000 Filipinos armed with rifles and bolos. He established his headquarters in the house of Dolendo and Maestro Siso at Mateuna and laid siege on the Spanish forces.

The situation became increasingly desperate as the besieging army grew and the Spanish forces dwindled. Exhausted, starving, afflicted by malaria, the Tayabas garrison ran out of medicine, ammunition and food. Several soldiers had died of hunger.

Bombarded daily for weeks by Malvar's army, Commander Pacheco eventually came to realize that holding out was futile and would only increase the number of deaths on their side.

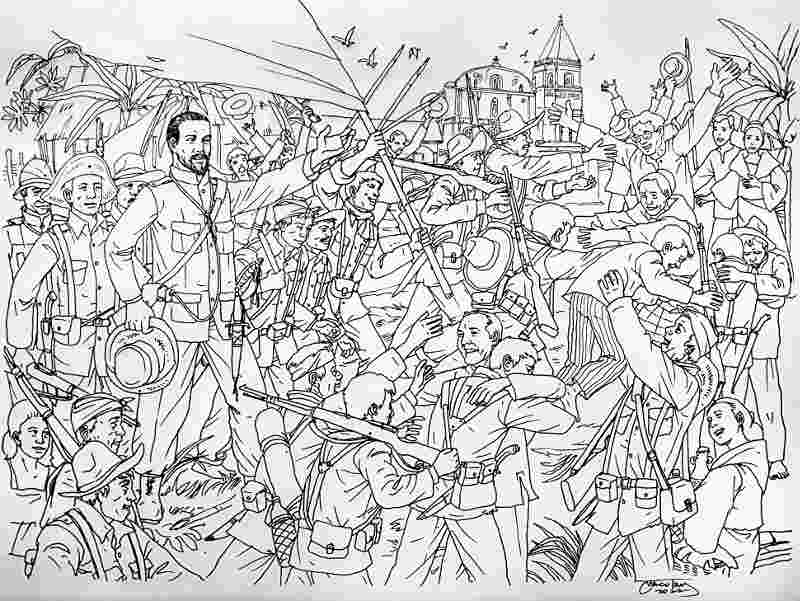

On August 15, 1898, Tayabas capitulated. The twenty officers and one hundred and seventy-five surviving Spaniards surrendered. (See Liberation of Tayabas).

As Gen. Miguel Malvar's army triumphantly entered the newly liberated city, the citizens of Tayabas shouted:

Tagapagpalaya ng lalawigan ng Tayabas.

Heneral Miguel Malvar, Viva San Miguel Arcàngel!, Viva Heneral Miguel Malvar!

Liberator of Tayabas province.

General Miguel Malvar. Viva San Miguel Archangel! Long live General Miguel Malvar!

It was only fitting that the liberator of Tayabas shared the name of the patron saint of the place he had set free from Spanish control. Malvar's revolutionary seal also bears the imagery of San Miguel Arcàngel. (See evolution of the seal).

Major Cornelius Gardener called the former insurgent, Malvar, who surrendered at Batangas province last April, to testify today before the board which is investigating the charges brought by Major Gardner concerning conditions in Tayabas province, Luzon. The board held its first meetings at Lucena, Tayabas province, but adjourned there to meet in Manila. The testimony given by General Malvar has created considerable surprise. He said that Tayabas province had been one of the best disciplined insurgent strongholds under his control, and that each municipality in the province obeyed him. He declared that he could have called 1,500 riflemen and 450 bolomen in Tayabas province, and this without counting upon the men he could have raised in other provinces; that the people in Tayabas obeyed well the orders issued by the American authorities as well as his own. He sent supplies to the insurgents, he said, and then after the lapse of a few days would notify the Americans that such supplies had gone out. This Malvar ordered the townspeople to do in order that they might not be suspected by the Americans of disloyalty. Each body of insurgents in Tayabas was supported by the town to which it belonged. General Malvar said also that the object of all his orders was to prolong the struggle indefinitely; consequently, the small engagement; the insurgents were only allowed to attach the Americans when they outnumbered them three to one, and in larger engagements only when they had a t least equal numbers.

Continuing his testimony, General Malvar said that the presence in an town of any native who was truly friendly to the American cause would have made it impossible for an insurgent body to exist in that town. To the best of his belief, he declared the insurgents had candidates in all municipal elections held in the provinces. General Malvar personally ordered the attack at Candelaria, in Tayabas, last December. In conclusion, the witness said that the insurrection in Tayabas and Batangas provinces had been broken up as a result of the methods adopted by Gen. J, Franklin Bell in conducting the campaign there.

- News article, June 18, 1902 (link to attachment)

The provinces of Cavite, Batangas, and Laguna may be considered together. They are the most thickly settled and richest in southern Luzon, the home of the Tagalos and the birthplace of the insurrection. The insurrection seems destined to meet its death in the place of its birth and to die hard.

The principal figure of the rebellion is General Malvar, a native of Batangas province, who claims to be the civil and military head of what remains of the insurrection. He proclaims himself the successor of Aguinaldo by the appointment of the committee in foreign parts, which committee, he says, was appointed by Aguinaldo in June, 1900, "to act in his place in case of his absence." Malvar has undoubtedly also the material support of a large number of high-class natives and foreigner in Manila and other large towns, who, while taking no active part against the Americans, are not satisfied with the course of events and probably not quite convinced as to the honesty of our intention, nor have they quite given up the hope of foreign intervention. They believe it well to keep alive a spark of insurrection with which to rekindle the flame of rebellion should opportunity offer.

J. F. Wade

Brigadier-General, U.S.A., Commanding.

Annual report of the Secretary of War v1 pt.7 (1900/01)